|

Mining in Cornwall Until the mid 19th. century there was a massive tin mining industry in Cornwall. Cornwall's tin industry collapsed when cheaper tin, from the Far East, flooded the world market. Thousands of Cornish families were thrown out of work and many of them moved to other mining parts of the English-speaking world. Some moved to the coal mining areas of Great Britain whilst others took the opportunity to start a new life in the New Worlds of the United States, Canada and Australia.Thousands of people chose to migrate to the colony of South Australia following the discovery of rich deposits of copper at Kapunda c.1844 and Burra c.1845. More rich deposits of copper were discovered at Moonta c.1859 and at Kadina c.1861. Many of the Cornish families were friends or relations, and they settled in the same area, thus earning the district a nickname 'Little Cornwall'. By the 1870s South Australia had replaced Cornwall as the leading copper producer in the British Empire. Kapunda and Burra mines were closed in the late 1870s. Moonta and Kadina were still being worked until 1923, and were big mines by world standards of the day. |

Tin working in Cornwall began in the Bronze Age, where veins of ore

were exposed by streams cutting across the moors. Tin is one of the

components of bronze, and for more than 2,000 years, tin mining was a

major industry in Cornwall. Even before the birth of Cist, Cornish

traders were exporting to Europe and the Roman Empire. The brasswork in

King Solomon's Temple is said to have been wrought from Cornish tin, and

an old legend has it that Christ himself visited Cornwall with his uncle,

Joseph of Arimathaea, a merchant who came to buy tin.

Tin working in Cornwall began in the Bronze Age, where veins of ore

were exposed by streams cutting across the moors. Tin is one of the

components of bronze, and for more than 2,000 years, tin mining was a

major industry in Cornwall. Even before the birth of Cist, Cornish

traders were exporting to Europe and the Roman Empire. The brasswork in

King Solomon's Temple is said to have been wrought from Cornish tin, and

an old legend has it that Christ himself visited Cornwall with his uncle,

Joseph of Arimathaea, a merchant who came to buy tin.

The name "Wheal" which prefixes many Cornish mine names comes from the Cornish word "whel", which means "tin mine". Sadly, the once great Cornish tin industry is now defunct - the last one to close being 'South Crofty' near Helston. However, preserved workings can still be seen, such as at the Poldark Mine. Years ago, the "tinners" were granted special privileges in Cornwall because of their contribution to the economy. Their history is packed with odd traditions and tales. In particular they were very wary about the spirits who lived in the mines - the knockers, buccas (imps) and spriggans. Stories of disembodied hands carrying candles, spirit voices warning of impending rock falls and ghostly black dogs and white hares prophesying certain disaster abound toughout Cornwall – perhaps not too surprising, as flickering candlelight was the tinners' only illumination until Cornishman Sir Humpy Davy invented his Miner's Lamp! Men, women and children worked in the mines. Women ('bal-maidens') did many of the above-ground tasks, and small children would fetch and carry and do odd jobs. At 12 years old, they could join their fathers underground. As the mines grew larger and more prosperous in the early 19thC, mining became a family tradition in the main mining areas such as West Penwith, where the granite rock masses yielded the largest amounts of tin and copper. Very little was wasted, and by-products included lead and arsenic. Cornish "hard-rock" men were in great demand wherever strength, stamina and skill were needed.

It was pitch black underground except for pools of light town by

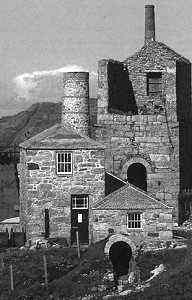

candles stuck There was always danger; rocks fell from the roofs, tunnels caved in, explosions caused disasters, and rotten ladders and planks tew many a miner to his death in deep holes and shafts. Medical services were primitive and expensive, and a miner too badly injured to work had to rely on charity. Every mining village had its little band of cripples sitting forlornly in the village square as a grim reminder of the cost of tin and copper. Surprisingly, however, they were generally cheerful. At a time when all life was hard, they did not consider themselves to be worse off than most. They sang on the way to work, and in the churches and chapels on Sundays; they had a natural ability to harmonise, and the sound of scores of men singing favourite hymns in harmony is well remembered by the older people of Cornwall. Levant & Geevor

Adjoining Levant is Geevor Mine, a treasure house of industrial archaeology. Geevor was the last working mine in the area, but closed in 1990. Now it is the site of an outstanding mine heritage centre. In the earliest gravel or stream works, the water was carried out in

wooden bowls, or was carried off from the In Charles I’s reign, there were complaints that the increased cost of drainage, added to the increased cost of materials, had brought about a period of great depression, and it was noted that both capital and labour were leaving mining for husbandry. Because of these difficulties, one pit after another was being drowned out and the future of the industry seemed very precarious. In 1710, John Costar successfully used a single large water-wheel to drain some of the deeper mines. His invention, however, was quite overshadowed by that of the steam engine, which resulted in a major change in the tin-mining industry. The first shallow diggings had been worked by ordinary workmen with little or no capital, but as the mines became deeper, greater investment was required to sink the shafts and keep them clear of wate. This meant the involvement of a new class of men from outside the mining districts, or at any rate distinct from the ordinary miners, who were induced to venture their money in the mines. Unfortunately, many mines were not well managed, and when difficulties arose, investors often withdrew their cash, and if a mine owner had to spend months searching for fresh lodes without earning a profit, money often ran out, resulting in closure, flooding and unemployment.

West Cornwall, full of working mines with their granite stacks, was the hub of the Industrial Age, especially in the area south of Redruth. From 1801 to 1830, Cornish mines produced on average two-thirds of the total world production of fine copper, and their prosperity peaked between 1850 and 1865, when most of the world's tin and copper came from the county. However, after this time, enormous deposits of tin and copper were discovered abroad, eventually resulting in the destruction of the Cornish mining industry and the emigration of thousands of miners and their families to the new world. Celia Feinnes - 1698. "I

went a mile further and soe came where they were digging in the Tinn

mines. there was at least 20 mines all in sight which employs a great many

people at work, almost night and day, but constantly all and every day

includeing the Lords day which they are forced to, to prevent the mines

being overflowed with water; more than 1000 men are taken up about them,

few mines but had then almost 20 men and boys attending to it either down

the mines digging and carrying the oare to the little bucket which conveys

it up, or else others are draineing the water and looking to the engines

that are draineing it, and those above are attending the drawing up the

oare in a sort of windlass as it is to a well; two men keeps turning

bringing up one and letting down another, they are much like the leather

buckets they use in London to put out fire which hang up in churches and

great mens halls; they have great labour and great expense to draine the

mines of the water with mills that horses turn and now they have the mills

or water engines that are turned by the water, which is convey'd on frames

as timber and truncks to hold the water, which falls down on the wheeles,

as an over shott mill - and these are the sort that turns the water into

severall towns |

| Special thanks to http://fp.berryman.plus.com/genealogy/mining.htm for this information |

By our standards,

life for the miner and his family was very hard. Cottages were tiny,

perhaps with only one room and a sleeping loft in the rafters for the

children. Water had to be fetched from the local pump, and the garden

provided the bulk of the food in the summer, with potatoes being the

staple item. Most miners also kept a few chickens and a cow for eggs and

milk. On the coast, there were also fish to catch, and it was not unusual

for several men to have shares in a small boat and to lay nets and crab

pots. Looking after the garden and animals and going fishing were spare time

occupations.

By our standards,

life for the miner and his family was very hard. Cottages were tiny,

perhaps with only one room and a sleeping loft in the rafters for the

children. Water had to be fetched from the local pump, and the garden

provided the bulk of the food in the summer, with potatoes being the

staple item. Most miners also kept a few chickens and a cow for eggs and

milk. On the coast, there were also fish to catch, and it was not unusual

for several men to have shares in a small boat and to lay nets and crab

pots. Looking after the garden and animals and going fishing were spare time

occupations. Considering the length of the miner's working day and the arduous nature

of the work, we can only wonder at their stamina. There were 3 eight-hour

daily shifts ("cores") in the mines from 0600, 1400 and 2200 s. Many men

walked up to 5 miles to the mine from their homes and, after climbing down

hundreds of yards of vertical ladders, walked a further mile or two to

actually began work. After 8 hours of backbreaking work in hot, cramped

and frequently wet conditions, they had to do it all again in reverse to

get home.

Considering the length of the miner's working day and the arduous nature

of the work, we can only wonder at their stamina. There were 3 eight-hour

daily shifts ("cores") in the mines from 0600, 1400 and 2200 s. Many men

walked up to 5 miles to the mine from their homes and, after climbing down

hundreds of yards of vertical ladders, walked a further mile or two to

actually began work. After 8 hours of backbreaking work in hot, cramped

and frequently wet conditions, they had to do it all again in reverse to

get home. to the front of

their canvas hats or placed on ledges on the walls. Men bought their own

candles and tools and, when pay day came, were often in debt for them to

the mine owner. There were several ways of earning money, but generally, a

miner was paid for the quality and quantity of good ore brought to the

surface. If he was fortunate, and had a dry, workable pitch with rich

lodes, he could earn a living wage; otherwise, he took home very

little.

to the front of

their canvas hats or placed on ledges on the walls. Men bought their own

candles and tools and, when pay day came, were often in debt for them to

the mine owner. There were several ways of earning money, but generally, a

miner was paid for the quality and quantity of good ore brought to the

surface. If he was fortunate, and had a dry, workable pitch with rich

lodes, he could earn a living wage; otherwise, he took home very

little. One of the greatest mines of the St. Just mining area

was Levant on the Pendeen coast.

One of the greatest mines of the St. Just mining area

was Levant on the Pendeen coast. working in a

'level', or trench, leading from the work to the river. However, by the

end of the 16thC, a period of shallow diggings in the stanniferous

gravel being worked out, shaft mining into the bedrock made mechanical

mining improvements essential in order to go deeper underground.

Techniques were still primitive; they used picks, hammers and iron wedges,

sometimes heating the rock surface by fire to split it open. (Gunpowder

was introduced, with several tragic results, in 1689.) Some mines reached

a depth of 300 ft, and German engineers were employed to drain the

workings: adits were driven into hillsides, and windlasses and water

wheels were used to power pumps. The adit was similar to the level only

driven tough the hill-side to meet the shaft at its foot. This last was

expensive and temporary, because as soon as the shaft was driven deeper

additional apparatus had to be used to raise the drainage to the level of

the adit. Various mechanical pumping devices worked by man-power were also

tried, but the severity of labour they entailed on the men working them

made them unsatisfactory and costly. Water wheels were used in some mines,

but as their power was limited a deep mine needed two or tee wheels, one

above the other, to clear it effectively.

working in a

'level', or trench, leading from the work to the river. However, by the

end of the 16thC, a period of shallow diggings in the stanniferous

gravel being worked out, shaft mining into the bedrock made mechanical

mining improvements essential in order to go deeper underground.

Techniques were still primitive; they used picks, hammers and iron wedges,

sometimes heating the rock surface by fire to split it open. (Gunpowder

was introduced, with several tragic results, in 1689.) Some mines reached

a depth of 300 ft, and German engineers were employed to drain the

workings: adits were driven into hillsides, and windlasses and water

wheels were used to power pumps. The adit was similar to the level only

driven tough the hill-side to meet the shaft at its foot. This last was

expensive and temporary, because as soon as the shaft was driven deeper

additional apparatus had to be used to raise the drainage to the level of

the adit. Various mechanical pumping devices worked by man-power were also

tried, but the severity of labour they entailed on the men working them

made them unsatisfactory and costly. Water wheels were used in some mines,

but as their power was limited a deep mine needed two or tee wheels, one

above the other, to clear it effectively. It

was steam power that eventually made deep mining possible. Greater power

being available, shafts were sunk much lower than ever before, enabling

copper, rather than tin, to be extracted - copper was then in great demand

for everything from kettles and kitchenware to copper-bottomed sailing

ships. (More money was actually made from mining copper than tin in

Cornwall).

It

was steam power that eventually made deep mining possible. Greater power

being available, shafts were sunk much lower than ever before, enabling

copper, rather than tin, to be extracted - copper was then in great demand

for everything from kettles and kitchenware to copper-bottomed sailing

ships. (More money was actually made from mining copper than tin in

Cornwall). I have seen about London Darby and Exeter, and many places

more; they do five tymes more good than the mills they use to turn with

horses, but then they are much more chargeable; those mines do require a

great deale of timber to support them and to make all these engines and

mills, which makes fewell very scarce here; they burn mostly turffs which

is an unpleasant smell, it makes one smell as if smoaked like bacon; this

oar is made fine powder in a stamping mill which is like the paper mills,

only these are pounded drye and noe water let into them as is to the raggs

to work them into a paste; the mills are all turned with a little streame

or channell of water you may step over; indeed they have noe other mills

but such in all the country, I saw not a windmill all over Cornwall or

Devonshire tho' they have wind and hills enough, and it may be its too

bleake for them."

I have seen about London Darby and Exeter, and many places

more; they do five tymes more good than the mills they use to turn with

horses, but then they are much more chargeable; those mines do require a

great deale of timber to support them and to make all these engines and

mills, which makes fewell very scarce here; they burn mostly turffs which

is an unpleasant smell, it makes one smell as if smoaked like bacon; this

oar is made fine powder in a stamping mill which is like the paper mills,

only these are pounded drye and noe water let into them as is to the raggs

to work them into a paste; the mills are all turned with a little streame

or channell of water you may step over; indeed they have noe other mills

but such in all the country, I saw not a windmill all over Cornwall or

Devonshire tho' they have wind and hills enough, and it may be its too

bleake for them."